Metaphor and life with a brain injury

It was a beautiful August morning in 2021. Kris Kuehl, as her mom would say, was ‘busy as a cranberry merchant’ preparing to start her day working as an orthopedic physical therapist when something fell and hit her on the head, creating a small but deep wound in the R frontal region of her skull. She can still feel the divot. She pushed pause on her day and was driven to the closest emergency room holding a towel to her head, feeling a little weird.

“I don’t know what makes the cranberry business so hectic, but I think it’s cute so I like to sprinkle it in sometimes. My mom is full of sayings like that and, at least in this instance, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree,” explains Kris. I’ve got lots of metaphors for life with a brain injury.” Keep reading and you’ll learn a few.

While in the ER, Kris was drowsy and napped most of the morning. She received a CT scan, was cleared of any emergent problems, and was given one stitch to her short but deep wound. The ER doctor advised that she probably had a concussion and recommended she should go home to rest and follow up with a primary care doctor if she wasn’t feeling better in a few days.

Kris continues, “After the ER, I went back to work to see two new patients who I did not want to cancel on. I figured if I only needed one stitch that it wasn’t a big deal, but it was more difficult than I expected. When I got home, I felt lousy but I still assumed that a good night’s sleep would have me well on my way to feeling better. That was also incorrect.

“The next day I woke up and still didn’t feel right. I was very tired, felt slowed down and wonky. But again, I thought ‘it was just a small wound, no big whoop’, so I went back to work. At 7am I was on a zoom call, but I had trouble processing what was being said. When it was my turn to talk, I couldn’t organize my thoughts. It was as if I’d been asked to explain Einstein’s theory of relativity. I just froze up and stammered.”

Within a couple of days Kris saw a primary care provider who created a plan including physical therapy, a few days off, and significant restrictions on her work hours & duties. Again, she expected to feel like her old self again soon, this time addending her expectations to be fine in a week or two. But even with less work and more breaks she was still struggling with her symptoms and daily activities.

Kris continues, “I set these goals – imaginary goals – like I’ll feel better in a month, or then I’ll be good to go by the holidays, but the holidays were horrible. I didn’t know what to make of it, it was very frustrating”. Her expectations for recovery were based on the fact that the majority of people with concussions/TBI recover within a few days to 3 months. Most of the rest are feeling better by the one-year mark. Also, Kris has a good track record of being able to accomplish just about every lofty goal she’d set. She received her clinical doctorate in Physical Therapy 12 years ago and, she won’t tell you unless somehow the topic of the world class discus throwing comes up, but she’s an Olympian and was a multi-time member of Team USA in the discus throw. She’s experienced the benefits of keeping her nose to the grindstone and has come back from her share of injuries.

“My ability to tolerate exercise was improving, which is a very good thing for brains, but it was a far cry from my pre-injury fitness level. And although I was gradually building back up my tolerance for chores and work, that aerobic improvement wasn’t carrying over to my tolerance for light, noise, screens, conversations, memory, etc., like I expected. I still had visual processing issues that were not coming around, I still felt some degree of lousy and wonky all the time. The stress and frustration from all of it was building.

Here’s an example of how much a blow to the noggin can affect physical function. Two weeks before her injury Kris completed an 11-mile day hike on the Superior Hiking Trail. Two days after her injury she couldn’t walk 2 blocks at a slow pace without a big spike in her heart rate or symptoms. This wasn’t because she was out of shape. It was because most of what it takes to walk any distance is mediated by the nervous system. And when the nervous system is not content it can cause other body systems to not work right. This is why it is important to work with a physical therapist (in addition to other therapies) to recover from a persisting head injury.

Science has taught us much about how sprains, strains and bones heal, so doctors and physical therapists have a pretty good idea of when it’s appropriate to be cautious and when it’s better to be aggressive with rehab. Regardless of the injury patients need to prod at their impairments by loading the affected system(s) enough to stimulate adaptation and change in the tissues. Physical therapists call this ‘poking the bear’ and it’s how the body heals. There will often cause some discomfort, and if it’s tendon, muscle or bone, there will probably be a little pain too and that’s OK if it’s just a little bit and it resolves well. Sometimes with musculoskeletal injuries people can get away with ‘waking up the bear’ which was something Kris also experienced during her athletic career. An injured brain on the other hand is not so keen on that.

She adds, “I thought I could push my recovery like I did when I had musculoskeletal injuries. That’s what ice and ibuprofen were for. But that’s not how it works for brain injuries. I learned the hard way – several times – about the sensitivity and agility of the brain bear. Even though I’m a physical therapist and I knew better, I was stubborn, and my brain was injured so there’s that. My brain was, and continued to be, a combination of work horse and diva. respect my symptoms. It wants to contribute and please, but it needs a little extra hand-holding and structure even now. This was especially true for a good 18 months I’d say as I was learning and re-learning the difference between a poke to the bear and a karate chop”.

But the brain is not nearly as well understood as the musculoskeletal system. Oftentimes imaging doesn’t shed much light on what to do when it’s not working right. Every patient with a brain injury presents with their own unique challenges and there is no standard protocol that works for everyone. “One halfway decent tool we have is our heart rates. My physical therapists helped me monitor it along with my symptom changes during our exercise sessions. From there we had a ballpark idea of what my heart rate limits should be when I was walking or doing chores. It was tricky at first because I could easily exceed my max limit before I felt any significant increase in my symptoms. So I started checking it sooner and learned the nuances of what I was feeling as I neared my threshold.”

Concussion/TBI symptoms must be respected. Kris does not recommend waking the bear. It is not fun. But she’d be the first to say that if you have a brain injury you will do it and you will do it often; most of the time, accidentally but sometimes on purpose out of necessity or frustration. It’s another part of the process for figuring out your limits. The downside is that once riled up it can take a lot longer for symptoms to calm back down, they start to stack up and it disturbs several other body functions like heart rate and rhythm, sleep, fight or flight response, emotions, etc.

“We know that initially rest is very important, but then patients need to get moving, back to work, back to life, etc. Finding the ‘sweet spot’ between doing too little and too much is the tricky part, and this is only learned through trial and error. My metaphorical chickens were always clucking and always coming home to roost. I didn’t understand what my sweet spot was or that it could change without warning. When you are struggling with an injury to the only organ you’ve got that is capable of sorting out all the details about how to treat it’s injury; well, seriously, you need a care team that knows a lot about that organ and how to help it.”

Within several weeks a colleague suggested to Kris that she make an appointment at the Hennepin Healthcare Traumatic Brain Injury Outpatient Program. By October she had her evaluation with Mark Winkler (Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation) and was referred to Speech-Language Pathology, a Clinical Psychologist, Neuro Optometry and eventually Occupational Therapy as part of a multi-faceted approach to her care. Each of these doctors and therapists work on the same floor making collaboration much easier. Even with all the bells and whistles that the TBI program has for assessment and treatment, Kris was most impressed by the compassionate care she’s received.

“I am so grateful for my HCMC team! Everyone is well versed in helping people with brain injuries, so they each have a deep understanding of what we are going through. There is just an atmosphere there that says ‘Hey, we know you probably don’t feel very good right now so we’re going to meet you where you are at. We’ll dim the lights and be mindful of our pace. We’ll give you time to talk and cry if you need. We will listen, believe what you have to say and help you through this’. That kind of compassionate care, especially with an injury that causes so many ‘invisible’ struggles, goes a long way.”

Kris notes that once her care team had a good handle on what her impairments were (and were not), their next order of business was to coach her on ways to make work and daily activities more tolerable and productive. Figuring out how to cope with a head injury requires the ability to learn new skills which, as you continue to read, will see is challenging.

Kris elaborates, “Early on, I was spending so much energy trying to live my life the way I was used to, that my brain didn’t have the resources to recognize my triggers and sensitivities, much less understand what to do about them. I was clueless to my own cluelessness. The only thing I could come up with was to close my eyes, and that was purely involuntary. I needed other people to cue me on very common-sense suggestions like; take some days off from work, put a pair of ear plugs in every bag and jacket pocket, swap out fluorescents for LED wherever possible. Even stopping at the grocery store was extremely difficult (and still isn’t easy) but it didn’t even occur to me to find other ways to get food until someone offered to go for me.

Kris explains that navigating work and life in a world that is tightly scheduled and bursting with stimuli is not easy for anyone, but it’s different and oftentimes harder for someone with a brain injury. Every now and then the world makes accommodations, but most of the time it doesn’t. As a result, they must find their own tools and methods for gaining some control of their surroundings.

“Grocery stores, I learned, are a minefield of small aggravators. You’ve got to get there and back, they are extremely well lit, almost everything is in aisles, you have to find what you’re looking for and make decisions in the midst of many moving people & parts, background music & beeps, and then you have to stand in line and check out before you’re allowed to leave. At first my way of controlling all of that stimuli was to stay home where it’s dark and quiet and defer those duties to someone else. Occasionally, I’d need to pop in for a couple things but I’d make it quick and stick with the small family-owned store in my neighborhood. Over time I was able to stay longer and even used shopping as a rehabilitation tool. I also own far more ballcaps than I ever thought would and I’m almost always wearing one.”

If you’re wondering what’s so hard about aisles, at least for Kris, it’s because moving around things that are nearby creates a continuously changing visual environment. There is a cost for the nervous system to buffer those changes. An injured brain has a very tight energy budget which makes processing things in the background more difficult and often results in more symptoms. Grocery stores challenged every sensitivity Kris had and she still uses the word ‘wonky’ to describe her primary symptom that continues to ebb and flow through her life.

“I go to a monthly support group for people with brain injuries and discovered, to my delight, a few of us use metaphors to describe what we’re feeling.” she continues. “Maybe it’s because we are trying to help those with uninjured brains to understand us. ‘Wonky’ is like floating on a raft and not feeling grounded. For the first year or so the waters were rough. There was always some degree of wind on my lake churning up waves and I sucked at keeping out of the choppiest areas. Over time, the winds are calming, my raft is better equipped, and I’ve learned how to paddle and navigate better.”

Addressing Kris’ visual disturbances was a team effort that included regular checkups with a neuro-optometrist and weekly visits with an OT, Nicole St. John. First, they found ways to manipulate her environment, so she had the brain energy to work on getting her eyes to behave like they were supposed to do. As that improved, they incorporated more complex and larger doses of activity to build her endurance. She worked with each branch of that team for over a year on a plan that started with special prescription glasses to improve her tolerance of computer work and transitions into bright environments. Her vision rehabilitation utilized both high-tech and old school devices that exercised Kris’s eye function. Her appointments always ‘tuned-up’ her symptoms but she knew that was part of the process.

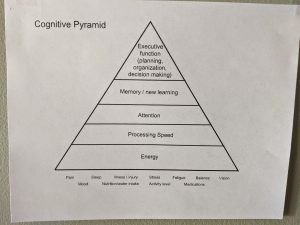

Early on Kris had frequent appointments with her speech therapist. Kris had heard good things about Helen Mathison, so she requested appointments with her. She didn’t know what to expect, especially given that her follow-up visits would be virtual and her ability to speak wasn’t that affected. She thought she’d get tongue twisters but what she really got was an in-depth tour of the cognitive pyramid.

“We worked a bit on word finding and pacing activities, but our prime focus was energy management. Helen is the one who taught me that ‘energy is king’ and that our time was better spent learning a variety of tools and strategies to structure my day in a way that best conserved energy for my now less efficient brain. We’ve continued to meet because figuring it out is complicated and I benefit from a little extra hand-holding putting it into practice. It was a very regular occurrence for me to think I had it down, but instead would overshoot only to find that the other shoe had dropped. They always dropped. So, my methods needed regular check in’s, adaptations and upgrades as I progressed. We could do speech drills till the cows came home, but if my brain was near “E” then it wouldn’t have mattered much. The good news is that I getting a lot better at it and my shoes don’t fall as far.”

The cognitive pyramid shows the hierarchy of brain operations where for any level of function on the pyramid to be at its best, the levels below it must be functioning optimally as well. Listed under the pyramid are common external factors that affect its foundation; energy. But training our brains to be in great shape is not necessarily a bottom to top process. It is more of an evolution of learning and adaptation that is forever moving in both directions.

The cognitive pyramid shows the hierarchy of brain operations where for any level of function on the pyramid to be at its best, the levels below it must be functioning optimally as well. Listed under the pyramid are common external factors that affect its foundation; energy. But training our brains to be in great shape is not necessarily a bottom to top process. It is more of an evolution of learning and adaptation that is forever moving in both directions.

Kris interprets it like this: “Brain injury or not, life forces all of us to continuously manage working at every level of the pyramid simultaneously. We don’t have the luxury of being able to focus only on improving our energy before we tackle processing speed and so on. On top of that, the metabolic energy it takes to run all layers of the pyramid is very expensive, especially the top-level functions. This leaves a tired, stressed out, improperly medicated, aging and/or injured brain at a disadvantage, so it has no choice but to be thrifty. A lack of energy means fatigue which slows down thinking making it harder to keep up and pay attention. When attending to things is tough, the ability to organize and remember them will be limited. This hampers information processing and decision making leading to a higher likelihood of error and delay in executive function – and more roosting chickens. So, the more I control my environment and the better I balance my tasks with my breaks, the more energy efficient I will be. Which should allow me to do more, perform better and have a lower symptom load. Likewise, structured opportunities to work on higher level tasks improves my memory and processing speed which, as long as I don’t over do it, builds my endurance.”

Kris keeps a couple of copies of the pyramid, the current version being very different than the original. Appreciate the humor. She hung it in her kitchen because she wanted to see it often and figure it out. It somehow ended up being the landing spot for most of her HCMC COVID screening stickers. She also finds it validating to know that there are sound reasons for why it’s hard to keep up.

being the landing spot for most of her HCMC COVID screening stickers. She also finds it validating to know that there are sound reasons for why it’s hard to keep up.

“I was in an energy crisis. The pyramid concept helps me make peace with my situation and symptoms. And it has helped me compartmentalize things so they are easier to attend to. I don’t like that I need extra breaks, strict routines, and a stripped-down calendar. I’m going to steal a metaphor from a colleague here, ‘it’s what’s on my menu’. Before my injury I could keep everything organized in my head with very few errors. Well, that is not on my menu anymore. Instead, I’ve had to turn into one of those people who actually uses the organizational tools that I buy. I have a whiteboard in my kitchen that I update every day or two so I have better command of my lists, time and tasks. I have a little notebook version of the white board that travels with me so I have a record of things that come up while I’m out of the house. Well, truth be told I have several notebooks because I often misplace them. And the calendar on my phone now shows everything I’m up to in color coded blocks so I can visualize the time they take up in my day. I still make mistakes either by miscalculating costs both over and under. And sometimes I just say ‘screw it, I’m ordering from the big menu’, but I’ve come far enough now that I’ve got more palatable options on my smaller version.

“Someone at my support group said that life after a brain injury should be described as a discovery rather than a recovery. I really like that metaphor. My daily challenge for progress has evolved from just getting by into discovering how to incorporate more volume, complexity, and spontaneity into my life without adding chickens to my existing flock or waking up the bears.”

There are many living around us with brain injuries. In Minnesota alone there are more than 100,000 survivors who are dealing with some form of disability. So, the odds are good that each of us regularly encounter people who are continually rediscovering the limits and opportunities of their own cognitive pyramid. Oftentimes we’ll never know that the person standing next to us in the grocery store is trying to manage their own unruly zoo at that very moment. Kris knows that people who’ve not dealt with the struggles of an ongoing head injury will never truly ‘get it’. “My Hennepin Healthcare providers and support group are helping me make peace with that.” She hopes that her story and metaphors can increase understanding of brain function and raise awareness of ways a ‘blow’ to that function can affect its entire ecosystem.